THE 80s

MUNICH - WHERE IT ALL STARTED

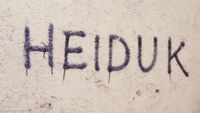

Who or what is the Heiduk? A mysterious tag that emerged in Munich during the late 1970s, sparking widespread speculations.

The word "Heiduk" began appearing on walls, bridges, and sidewalks across neighborhoods like Schwabing and Lehel, with its origins traced back to a commune in the Schlachthofviertel. Probably it was the commune’s landlord (named Heiduk) which made the group initially spray his name as a prank to annoy him. The tag gained momentum as others replicated it throughout the city, unaware of its meaning, turning it into a cultural phenomenon. Media outlets and residents speculated wildly—some linked it to Yugoslavian football clubs, while others saw it as an early form of graffiti. Despite the buzz, the true identity of the initial taggers remains unknown, and the meaning of "Heiduk" is still debated, marking it as a foundational moment in Munich’s graffiti history.

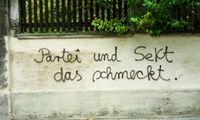

During the height of the Cold War in the early '80s, Munich's walls were covered with slogans, personal and political statements, anarchy symbols and peace signs criticising local and world politics (especially those of US president Ronald Reagan).

"Imagine there is war and nobody goes," a popular slogan during the 80s, modified from the original by US poet Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) "Sometime they'll give a war and nobody will come".

In 1981, the Munich police compared the political slogans with a “wall newspaper in Beijing”. (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14.08.1981)

"The self-proclaimed 'spray artists' are becoming a growing problem in Munich", so the city's building department: ”Graffiti has become a fashion." 500 graffiti were removed in 1981, at a cost of 50.000 Deutsch Marks to clean the city's buildings. Already then authorities were annoyed, one person was quoted of complaining about the graffiti sprayers, that they should "lick each letter off the wall".

(translated article below)

90 DEGREES OF HOT WATER STEAM is used to wash the paint smears from a stone in Flaucherpark. Beforehand, the worker treated the sprayed words with a special paste that dissolves the paint from the stone.

A significant site of photographic innovation in Munich, the Agfa factory underwent critical changes in 1982 and 1983. Originally a cornerstone of the Agfa-Gevaert Group, the Munich facility had been a global hub for camera and photographic equipment production since the early 20th century. However, by 1982, financial difficulties had led to the closure of the camera production line, impacting around 3.200 workers in Munich.

The term "No Future" originates from the punk rock movement of the 1970s, most notably as a slogan associated with the British punk band Sex Pistols. It is derived from their 1977 song "God Save the Queen," which includes the line "No future in England's dreaming." The phrase encapsulated the disillusionment, nihilism, and frustration of British youth during a period of economic stagnation, high unemployment, and social unrest in the UK.

In 1982, the Munich newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung reported on the authorities' problematic situation concerning graffiti, with the headline "Quote makers cost the city a lot of money". In the article the costs are revealed, quoting police and city employees:

"This year [1982], we’ve already spent nearly 70,000 DM by mid-November on removing graffiti, stickers, and posters." That’s already 20,000 DM more than the entire previous year [1981]".

Further the article reveals about a special company:

"No wonder a company has already specialized in removing graffiti. It goes by the fitting name "Parolex."

"Quote makers" cost the city a lot of money

"Sprüchemacher kostet die Stadt viel Geld", Andreas Schmidt, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 27.12.1982

In Munich's Flaucherpark, a man in a blue overall is brushing a sticky, pink paste onto an old, weathered memorial stone. The worker is trying to remove a black spray-painted anarchy symbol—an "A" with a circle around it—and the word "Punk" scrawled in large letters on the stone pillar. The "slogan remover" has plenty of work in the park: almost all the trash cans and benches are defaced with graffiti, swastikas, and slogans. Self-proclaimed "spray artists" are becoming an increasingly significant problem in Munich. "Graffiti has become a trend," says Karlheinz Puchta from the city's construction department. Last year alone, around 500 instances of vandalism had to be cleaned from municipal structures, costing taxpayers 50,000 Marks for this type of property damage.

"In the subway stations, the spraying really took off last year," says Isolde Zins from Munich's public transport authority. "This year, we’ve already spent nearly 70,000 DM by mid-November on removing graffiti, stickers, and posters." That’s already 20,000 DM more than the entire previous year. The Königsplatz art station, ironically, is the most heavily targeted: "The columns and entrances have been defaced thirteen times already." The Nordfriedhof and Scheidplatz stations are also particularly affected by these "slogan sprayers." "This is probably because they aren’t constantly monitored by conductors." As a result, the "graffiti culprits" are rarely caught: "The subway cleaning crew usually doesn’t notice until the next morning."

Specialized Company Hired

No wonder that a company has now specialized in removing slogans. It goes by the name of "Parolex". And as the municipal workers often can't get rid of the graffiti, the city has hired them to keep the subway and other public buildings clean. The "Saubermänner" then collect 50 marks from the city per square meter of cleaned area. In return, walls, litter bins and stones are first smeared with the pink cleaning agent, as in Flaucherpark. The dissolved paint then only needs to be sprayed off with hot water. No wonder a company has already specialized in removing graffiti. It goes by the fitting name "Parolex." Since municipal workers often can’t remove the vandalism, the city has hired this company.

Less and less original

Once a Wall Is Defaced...

Although the "slogan sprayers" keep the graffiti removers busy at the moment, Tilman Steinke, the Munich manager of "Parolex," believes: "This is a business that ruins itself. Once we’ve cleaned the graffiti, the sprayers usually don’t dare touch the 'virgin' wall again. But if a wall is already defaced, the spraying just keeps going."

Students Sacrificed Free Time

Precise boundaries drawn

As with the schools, the people from "Parolex" are not allowed to work in the S-Bahn area. Because there, too, the Bundesbahn paints over the signs itself. This means that a slogan on a staircase that extends from the subway area into the suburban train area is only removed right up to the border of the subway area. Normally it always takes about two days from the discovery of a sprayed slogan to its removal. Only when slogans against the Bavarian Minister President are sprayed on public buildings does "Parolex" have to work faster. Steinke said: "We have to react immediately. If someone has sprayed anti-Strauß slogans, then there's fire on the roof. Then we should go out late Friday afternoon if possible."

Again and Again for Eva

There are also "slogan sprayers" who produce nicer messages than insults. For example, someone repeatedly painted love declarations, flowers, and hearts addressed to an Eva on the walls of the Implerstrasse subway station, always in the same spray-paint handwriting. Steinke recalls: "After about three months, it suddenly stopped. He probably broke up with the girl or decided it wasn’t worth it anymore." Young women, in particular, often wanted these sprayed love declarations to remain. Generally, though, Munich residents don’t take kindly to graffiti, whether it’s a love note or a political slogan. When workers remove graffiti, they often hear blunt comments like: "If only we could catch those vandals. They should have to lick off every single letter."